NBA

NBA Sunday: For Warriors, Sacrifice Starts at the Top

It’s a Warriors World, and we’re all just living in it.

Say what you want about Steve Kerr and company—at the very least, they’re consistent.

As a unit, the Warriors believe in strength in numbers and selflessness. Collectively, they believe in sacrificing for the betterment of the team, and at the end of the day, that is what truly makes them great.

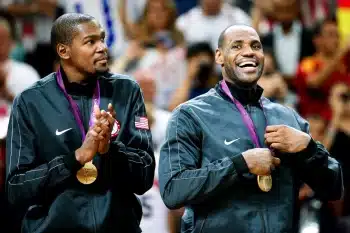

Draymond Green doesn’t complain about a lack of touches, he just kills himself in pursuit of earning a win. Klay Thompson doesn’t seem to be too bothered by the fact that Kevin Durant has supplanted him in the team’s hierarchy, he just works on his game and plays tough defense.

From top to bottom, this is the Warriors. They ride together, they die together.

It’s good to see that majority owner Joe Lacob isn’t as hypocritical as scores of other owners across the NBA.

* * * * * *

One thing that is rarely missed in the NBA is the opportunity to criticize a player for making a decision that doesn’t seem to be in the best interests of those around him. LeBron James and his defection to Miami serves as an example, as does Kevin Durant and his decision to chase championships in Oakland.

Long before then, though, back in 2008, there was another prime example. It involved Elton Brand and his decision to sign with the Philadelphia 76ers.

Coming off of a seven-year stint with the Los Angeles Clippers, Brand had grown into one of the NBA’s top power forwards. Then, during the final year of his contract, Brand ruptured his Achilles tendon. He managed to appear in just eight games. He felt his mortality and, at 28 years old, sought to secure his financial future to the largest extent possible.

Depending on who you ask, the account of what happened next differs. There are some that believe that Brand assured the Clippers that he would return to the team if they strengthened their roster while others maintain that Brand made no such promise. In an attempt to appease him, the Clippers signed Baron Davis away from the Golden State Warriors, but Brand surprised everyone when he let it be known that he decided to head back to his native east coast and join the Philadelphia 76ers. The Sixers, after all, offered Brand $7 million more than the Clippers.

Aside from Brand, over the years, we have seen critiques lobbied at just about any player who put himself first when it came time to getting paid. As a basketball culture, we are taught that selflessness—even when it comes to getting paid—is a requirement on the part of the player.

When it comes to increasing profit margins and maximizing returns on investment, though, league owners have long enjoyed the support of the public and media alike.

Hey, it’s just business, after all.

Over the years, whether it be the Chicago Bulls, Phoenix Suns, Oklahoma City Thunder or Miami HEAT, when owners are reluctant to become or maintain their status as luxury tax teams, they often jettison talented players. The gross majority of the time, that results in a weakened team that is less equipped to dominate or continue to dominate, as the case may be. Despite the fact that franchise values continue to skyrocket, owners who willingly let their talent leave don’t give back any of the television money they get, nor do they give season ticket holders back any refund. Face values of tickets are never lowered.

The gross majority of times, the saved money goes into ownership’s pockets, but few challenge the practice.

Truth be told, most NBA owners are billionaire businessmen who made fortunes outside of the game of basketball. Take Steve Ballmer and Paul Allen as examples. Allen, a co-founder of Microsoft, is the current owner of the Portland Trail Blazers. Ballmer, coincidentally, served as the CEO of the company for 14 years. The two men each have an estimated net worth of over $20 billion.

In order to amass such a fortune, one needs to develop a hatred of profit losses, and that’s been consistent from owner to owner. When a player chases the bigger payday, the public is taught to view his pursuit as being selfish, but when an owner opts to choose wider profit margins over keeping his talented players in place, we are quickly reminded that this whole thing is just a business.

At least to this point, Lacob has stepped up in a monumental way.

* * * * * *

Amazingly, even with Kevin Durant added to the roster, the Warriors ended last season with a payroll of a shade less than $100 million. This was possible mainly because of the team-friendly, four-year, $44 million contract that Stephen Curry signed back in July 2013.

For perspective, the following teams each had higher payrolls than the Warriors last season: the Cleveland Cavaliers, Charlotte Hornets, Dallas Mavericks, Detroit Pistons, Los Angeles Clippers, Memphis Grizzlies, Miami HEAT, New York Knicks, Orlando Magic, Portland Trail Blazers, San Antonio Spurs, Toronto Raptors and Washington Wizards.

Amazingly, as the Warriors have become the first NBA team to win at least 65 games in three consecutive seasons, win an NBA record 73 regular season games and win two NBA Championships, they haven’t been one of the teams that have paid heavy luxury taxes. In fact, for the 2016-17 season, despite adding Durant to the team, the Warriors’ $99 million payroll was nowhere near luxury tax threshold of $113 million.

Heading into this offseason, the question as to whether or not Lacob and his group would be amenable to keeping their core together and dive deep into luxury tax territory was a bit of an unknown. It would have been easy for ownership to come to the same conclusion that Micky Arrison and his HEAT did many moons ago as it related to Mike Miller and Joel Anthony. That is, Lacob could have concluded that both Andre Iguodala and Shaun Livingston were luxuries that the Kevin Durant version of the Warriors just couldn’t afford.

Kudos to them for concluding otherwise.

With Curry’s new deal and, more importantly, the agreements to re-sign Iguodala and Livingston, once Kevin Durant re-signs with the club, the Warriors will become a luxury tax team and will likely remain one so long as the core of Curry, Durant, Thompson, Green, Iguodala and Livingston remains intact.

On July 1, the league announced that the salary cap for the 2017-18 season is about $99 million, with the luxury tax threshold set at $119 million.

In the first year of Curry’s new deal, he will earn about $36 million. Combined with the salary commitments the Warriors have to the players they have under contract (which includes Klay Thompson and Draymond Green), the team was looking at a $75 million payroll before coming to terms with Durant, Iguodala or Livingston.

Since news of Curry’s new contract came to light, news broke that the Warriors agreed to bring Iguodala back for about $15 million per year, while Livingston agreed to terms of an $8 million commitment. That puts the Warriors current payroll at about $98 million.

Using a salary cap mechanism referred to as the “Non-Bird” exception, the Warriors can easily offer Durant a new deal that would pay him $32 million for the 2017-18 season. It is widely assumed that Durant will return on such a deal, and his tentative agreement to do so, many believe, was a prerequisite for the Warriors bringing Iguodala and Livingston back. Once Durant’s expected $32 million salary is added to the ledger, the team will be looking at a payroll of about $130 million—$11 million over the luxury tax threshold.

The payroll figure of $130 million includes commitments to Curry, Durant, Green, Thompson, Iguodala, Livingston, Kevon Looney, Damian Jones and Pat McCaw. Although the team has a handshake agreement with David West, other notable cogs of the championship-winning team (Zaza Pachulia, JaVale McGee and Ian Clark, for example) are unsigned. Whether or not additional members of their championship team return, in all likelihood, the Warriors will be looking at a payroll somewhere around $140 million for the 2017-18 season, assuming Durant does re-sign. Being about $20 million over the luxury tax threshold could result in the Warriors having a luxury tax liability of somewhere around $40 million.

In other words, by retaining their core, the Warriors have made themselves a tax team and, in all likelihood, will see their luxury tax bill increase over the coming years.

The decision to do that, while seemingly an easy one to make, is one worth applauding on the part of Lacob. Specifically with regard to Iguodala and Livingston. In the want to maximize profits and keep luxury tax bills down, many other NBA owners would have concluded that they were cogs that were just a bit too expensive to keep.

Fortunately, for the Warriors’ management, selflessness and sacrifice, apparently, aren’t things that should only be expected of players.

* * * * * *

As the rest of the NBA tries to catch up and overthrow this potential dynasty before it actually begins, those that think that the Warriors are bad for basketball and competitive balance should keep one thing in perspective: the team has absolutely made it cool to sacrifice for one another.

With all credit due to Joe Lacob and his business partners, apparently, that edict extends all the way to the top.